Real Woman | Capital Health | Fall 2014

NERVES OF STeel

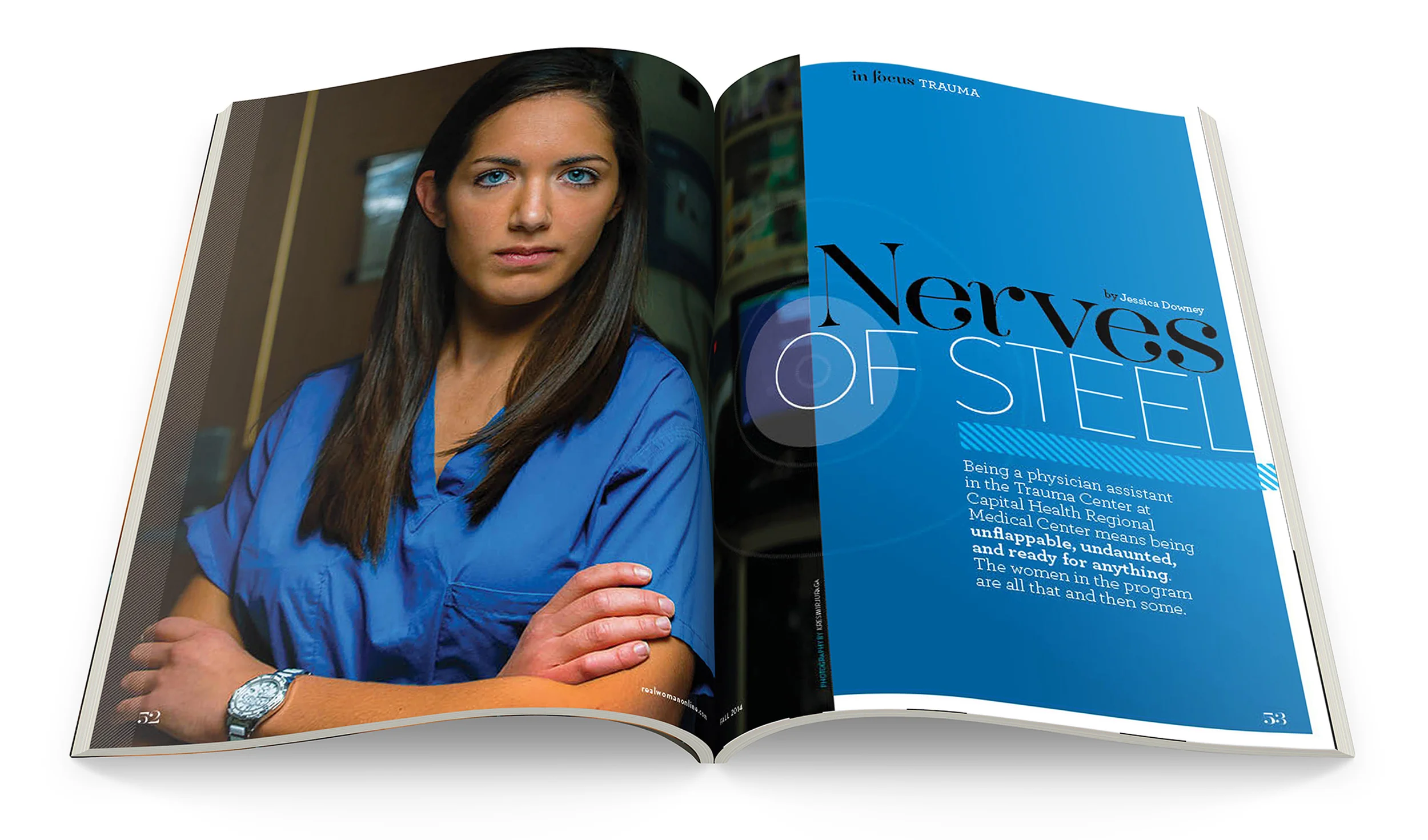

Being a physician assistant in the Trauma Center at Capital Health Regional Medical Center means being unflappable, undaunted, and ready for anything. The women in the program are all that and then some.

To us, it’s a gas explosion, an overturned tractor trailer, or a violent assault. It’s shattered glass, a gunshot wound. It’s something gone terribly wrong. It’s bloody and scary. It’s havoc—it’s trauma. But to them, it’s what they do, and they

love it.

On any given day (and night), several of the nine physician assistants (PAs) working in the Trauma Center at Capital Health Regional Medical Center in Trenton are assisting in the operating room, suturing wounds, putting in chest and tracheostomy tubes and central lines, casting, splinting, doing rounds in the Trauma Intensive Care Unit and the Surgical Trauma Unit, and basically performing whatever tasks are required to keep their trauma patients alive and well. “If you’re badly injured enough that you need to be taken to trauma, we take care of you from the minute you walk in to the minute you leave,” says 37-year-old Jennifer Wysocki. “That’s the best part of the job. We’re not just focused on one aspect of a patient’s care. We take the patients from injury to the point when they can hopefully leave the hospital.”

Once PAs receive their certification, they can practice medicine with physician supervision anywhere in the United States, with state-by-state licensure. They typically conduct physical exams, diagnose and treat illnesses, order and interpret tests, counsel on preventive health care, assist in surgery, and write prescriptions. And in trauma—where the stakes are as high as it gets—they often transition at a moment’s notice, with just a wailing alarm to signify the change. “PAs are a key component of our team,” says LF D’Amelio, M.D., FACS, the medical director of the Trauma Center. “Their skills span the entire spectrum of trauma care, including resuscitation, assisting at operations, and helping manage critically ill patients in the ICU and trauma floor. They have a broad range of cognitive, technical, and social skills and are a great comfort to our patients. They are largely responsible for the excellent outcomes at the Trauma Center.”

The Trauma Center at Capital Health is the regional referral center for injured patients in Mercer County and adjacent parts of Somerset, Hunterdon, Burlington, and Middlesex counties, as well as nearby areas of Pennsylvania, so the alarm sounds pretty often. So they have to be ready for anything because one minute they are doing rounds and the next they could be trying to revive a patient.

“All these women have a certain personality where they don’t balk under pressure. If you freeze up when Dr. Dennis Quinlan is trying to bring someone back from the dead in the trauma bay, then you’re not meant for this job. You can’t be,” says Wysocki. “You have to look past the bone hanging out of the leg and focus on what’s going to kill the patient first, and all of these ladies do that very well.”

Home of the Brave

Wysocki, who has been a PA for 12 years, with Capital Health for 6, says trauma tends to draw stoic individuals who crave that never-a-dull-moment kind of job. In emergency situations, when most people begin to panic, they are clearheaded. First-year PA Abigail Gonnella, 25, says that’s exactly the mind set that led her here. “I was a paramedic before I started PA school. My favorite calls were always the traumas, so when I would get dispatched to someone with a partial amputation, that would get my heart running,” she says. “When I rotated here as a student, I got to see what happened beyond picking up patients where they got hurt and dropping them in someone else’s hands. I got to see the whole continuum from the OR to the floor to discharge, and I loved it.”

While the 12-hour day and night shifts are tough—sometimes grueling—the PAs display a pride in their jobs and camaraderie between them that’s almost impossible to miss. In part that’s because in the Trauma Center, where PAs have been working since 2007 at Capital Health, the standards and expectations are exceptionally high, and the work is intense and demanding. “There are days when you want to pull your hair out because it’s nonstop,” says Janice Howze, 57, who has been a trauma PA for 5 years. “But I love it. Every day is so interesting, and the people I work with are incredible. The attending physicians, no matter what, if you’re scratching your head over something, they are so helpful and supportive. It’s not that we need constant supervision, but they are there for you. It makes us want to get up and come to work every day.”

Jamie Mora, 37, says her co-workers in trauma are like family. “Everybody takes care of each other. There’s no slacking off,” she explains. “You would never think of saying, ‘Eh, I’m not going to go see those patients because someone else is coming in at 7 o’clock.’ You get as much done as you can because you never know in the next minute if there will be two or three traumas, especially at night. In trauma, everyone is so focused. You need to perform as a team, and we definitely do that here.”

While the PAs at Capital Health know they need to leave the intensity—and often pain—of the Trauma Center behind when they leave, all of them have a patient or two who have stayed with them long after they’ve gone. For some of them, it was the first patient they admitted or the first one who died on their watch. But sometimes, it’s the one that hits too close to home. “The one that stays with me is a woman who was about my age who had kids,” says Wysocki. “She was an innocent bystander, and she got crushed by a car. I was working on her for a long time, and I lost her, and I never forgot that.”

Howze, who describes herself as having the “stiffest upper lip in trauma,” says even she broke down during a case a few months ago. “We had a 19-year-old who came in as an alert in an attempted suicide. He was here for about 2 weeks. We had to do all the brain studies on him to prove that he had already passed. Telling the parents—who were such lovely people—that he was gone was really heartrending. Having to tell those parents that their child was brain-dead—the entire department was on the verge of tears.”

The case that haunts Mora was a child. “A guy was driving his kids home, and they were in an accident. We had to transfer the little boy out—and he didn’t make it. His father died. I had to speak to the family because I speak Spanish. I had to tell the woman that her husband died,” she says. “Sometimes, no matter how hard you try, you take things home. But most times, you have to leave it here. There are other patients who need you.”

And sometimes, just the magnitude of the situation gets imprinted on their psyches. In March of this year, during Gonnella’s first week as a PA in trauma, a gas explosion rocked a condo community in Ewing, N.J., and the critical patients were brought to the Trauma Center. “I came to find out that the same company that had this gas explosion was the one my boyfriend was working for, so it was his co-workers who were brought to us,” she recalls. “It was my fourth day, so that’s something I’ll never forget.”

Tiffany Day-Neutill, 28, says being impacted by some of what happens in the Trauma Center is human nature, and not something they can ever truly bypass. “It’s hard working in trauma, seeing what we see, and not to take it home. As much as I try, when I have a bad trauma, it’s tough not to make it personal. You see someone who is your mother’s age, and it brings you back. You see someone younger than you who passes away, and it’s hard not to feel some of that,” Day-Neutill says. “My first one that died on me, I will never forget.”

A Matter of Trust

But while the lasting memories of losing patients in trauma can be a strain, the day-to-day successes and the trust and autonomy they get—and earn—from the doctors is incredibly rewarding. And in trauma—where things can get hectic in a millisecond—that trust is essential, says Mora. “My first couple months here, I was finally on my own up in the OR with Dr. Quinlan. We were doing a trach, and the trauma alert went off,” Mora recalls. “Dr. Quinlan was like, ‘OK, Jamie. We’re going to suture, and I’m out of here.’ He went down to the trauma bay, and I finished up. It’s a lot of trust from the physician that he knows what I’m doing.”

For her part, Wysocki has no doubt that all of the PAs know exactly what they are doing and are prepared for anything. In addition to getting their bachelor’s and master’s degrees, passing medical boards every 10 years, and obtaining their certifications and state licenses, they also have months of training in the Trauma Center before they can admit patients. And they bring different backgrounds and specialties, which they share with each other. “Most of us started as new grads, but Christina and Jen worked in surgery before, Janice worked in medicine and surgery,” says Day-Neutill. “Jen had spine experience, which was great. Chrissy brought neurosurgery. And Janice had everything. So as a new grad, it was this influx of knowledge, which is invaluable.”

Training the PAs and readying them for autonomy in the most difficult circumstances—when life is on the line—is a point of pride for Wysocki. “They all started as new grads, and they all needed to be trained, so when they do something good—they catch something I was going to miss—I feel like I’m taking pride in my own children. It’s like, ‘Tiffany was able to get the line in. Yes! Abby got a chest tube in! Yay!’

“I could have this job forever and be very happy.”